There is a story, regrettably apocryphal, about Napoleon and the Great Pyramid. When Bonaparte visited Giza during his Nile expedition of 1798 (it goes), he determined to spend a night alone inside the King’s Chamber, the granite-lined vault that lies precisely in the center of the pyramid. This chamber is generally acknowledged as the spot where Khufu, the most powerful ruler of Egypt’s Old Kingdom (c.2690-2180 BC), was interred for all eternity, and it still contains the remains of Pharaoh’s sarcophagus—a fractured mass of red stone that is said to ring like a bell when struck.

The Great Pyramid–built for the Pharaoh Khufu in about 2570 B.C., sole survivor of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world, and still arguably the most mysterious structure on the planet. Photo: Wikicommons

Having ventured alone into the pyramid’s forbidding interior and navigated its cramped passages armed with nothing but a guttering candle, Napoleon emerged the next morning white and shaken, and thenceforth refused to answer any questions about what had befallen him that night. Not until 23 years later, as he lay on his death bed, did the emperor at last consent to talk about his experience. Hauling himself painfully upright, he began to speak—only to halt almost immediately.

“Oh, what’s the use,” he murmured, sinking back. “You’d never believe me.”

As I say, the story is not true—Napoleon’s private secretary, De Bourrienne, who was with him in Egypt, insists that he never went inside the tomb. (A separate tradition suggests that the emperor, as he waited for other members of his party to scale the outside of the pyramid, passed the time calculating that the structure contained sufficient stone to erect a wall around all France 12 feet high and one foot thick.) That the tale is told at all, however, is testament to the fascination exerted by this most mysterious of monuments–and a reminder that the pyramid’s interior is at least as compelling as its exterior. Yes, it is impressive to know that Khufu’s monument was built from 2.3 million stone blocks, each weighing on average more than two tons and cut using nothing more than copper tools; to realize that its sides are precisely aligned to the cardinal points of the compass and differ one from another in length by no more than two inches, and to calculate that, at 481 feet, the pyramid remained the tallest man-made structure in the world for practically 4,000 years—until the main spire of Lincoln Cathedral was completed in about 1400 A.D. But these superlatives do not help us to understand its airless interior.

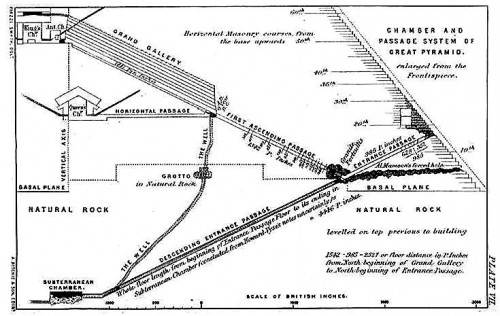

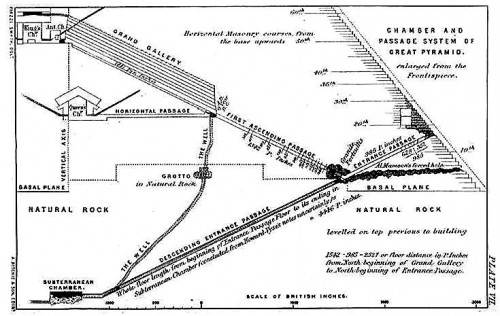

The interior of the Great Pyramid. Plan by Charles Piazzi Smyth, 1877. Click to view in greater definition.

Few would be so bold as to suggest that, even today, we know why Khufu ordered the construction of what is by far the most elaborate system of passages and chambers concealed within any pyramid. His is the only one of the 35 such tombs constructed between 2630 and 1750 B.C. to contain tunnels and vaults well above ground level. (Its immediate predecessors, the Bent Pyramid and the North Pyramid at Dahshur, have vaults built at ground level; all the others are solid structures whose burial chambers lie well underground.) For years, the commonly accepted theory was that the Great Pyramid’s elaborate features were the product of a succession of changes in plan, perhaps to accommodate Pharaoh’s increasingly divine stature as his reign went on, but the American Egyptologist Mark Lehner has marshaled evidence suggesting that the design was fixed before construction began. If so, the pyramid’s internal layout becomes even more mysterious, and that’s before we bear in mind the findings of the Quarterly Review, which reported in 1818, after careful computation, that the structure’s known passages and vaults occupy a mere 1/7,400th of its volume, so that “after leaving the contents of every second chamber solid by way of separation, there might be three thousand seven hundred chambers, each equal in size to the sarcophagus chamber, [hidden] within.”

But if the thinking behind the pyramid’s design remains unknown, there is a second puzzle that should be easier to solve: the question of who first entered the Great Pyramid after it was sealed in about 2566 B.C. and what they found inside it.

It’s a problem that gets remarkably little play in mainstream studies, perhaps because it’s often thought that all Egyptian tombs—with the notable exception of Tutankhamun’s—were plundered within years of their completion. There’s no reason to suppose that the Great Pyramid would have been exempt; tomb-robbers were no respecters of the dead, and there is evidence that they were active at Giza—when the smallest of the three pyramids there, which was built by Khufu’s grandson Menkaure, was broken open in 1837, it was found to contain a mummy that had been interred there around 100 B.C. In other words, the tomb had been ransacked and reused.

|

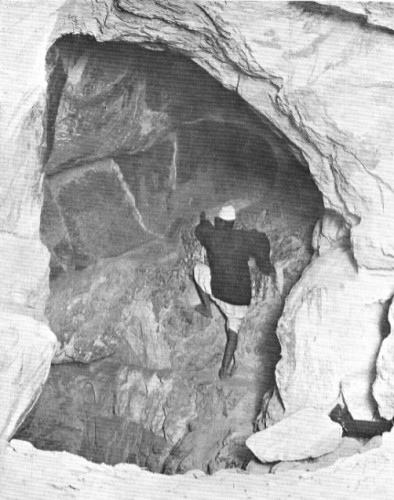

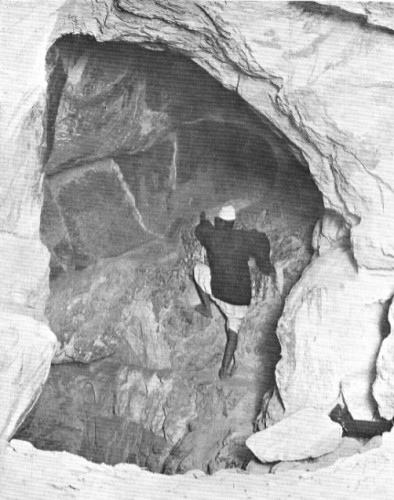

The subterranean chamber in the Great Pyramid, photographed in 1909, showing the mysterious blind passage that heads off into the bedrock before terminating abruptly in a blank wall after 53 feet. |

The evidence that the Great Pyramid was similarly plundered is more equivocal; the accounts we have say two quite contradictory things. They suggest that the upper reaches of the structure remained sealed until they were opened under Arab rule in the ninth century A.D. But they also imply that when these intruders first entered the King’s Chamber, the royal sarcophagus was already open and Khufu’s mummy was nowhere to be seen.

This problem is one of more than merely academic interest, if only because some popular accounts of the Great Pyramid take as their starting point the idea that Khufu was never interred there, and go on to suggest that if the pyramid was not a tomb, it must have been intended as a storehouse for ancient wisdom, or as an energy accumulator, or as a map of the future of mankind. Given that, it’s important to know what was written by the various antiquaries, travelers and scientists who visited Giza before the advent of modern Egyptology in the 19th century.

Let’s start by explaining that the pyramid contains two distinct tunnel systems, the lower of which corresponds to those found in earlier monuments, while the upper (which was carefully hidden and perhaps survived inviolate much longer) is unique to the Great Pyramid. The former system begins at a concealed entrance 56 feet above ground in the north face, and proceeds down a low descending passage to open, deep in the bedrock on which the pyramid was built, into what is known as the Subterranean Chamber. This bare and unfinished cavern, inaccessible today, has an enigmatic pit dug into its floor and serves as the starting point for a small, cramped tunnel of unknown purpose that dead-ends in the bedrock.

Above, within the main bulk of the pyramid, the second tunnel system leads up to a series of funerary vaults. To outwit tomb robbers, this Ascending Passage was blocked with granite plugs, and its entrance in the Descending Passage was disguised with a limestone facing identical to the surrounding stones. Beyond it lies the 26-foot-high Grand Gallery, the Queen’s Chamber and the King’s Chamber. Exciting discoveries have been made in the so-called air shafts found in both these chambers, which lead up toward the pyramid’s exterior. The pair in the Queen’s Chamber, concealed behind masonry until they were rediscovered late in the 19th century, are the ones famously explored by robot a few years ago and shown to end in mysterious miniature “doors.” These revelations that have done little to dampen hope that the pyramid hides further secrets.

|

|

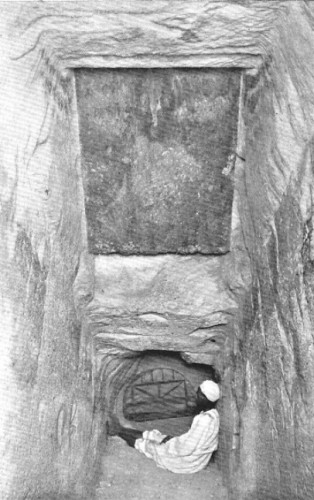

The forced tunnel in the north face of the Great Pyramid, supposedly dug on the orders of Caliph Ma'mun early in the ninth century. |

It is generally supposed that the Descending Passage was opened in antiquity; both Herodotus, in 445 B.C., and Strabo, writing around 20 A.D., give accounts that imply this. There is nothing, though, to show that the secret of the Ascending Passage was known to the Greeks or Romans. It is not until we reach the 800s, and the reign of an especially curious and learned Muslim ruler, the Caliph Ma’mun, that the record becomes interesting again.

It’s here that it becomes necessary to look beyond the obvious. Most scholarly accounts state unequivocally that it was Ma’mun who first forced his way into the upper reaches of the pyramid, in the year 820 A.D. By then, they say, the location of the real entrance had been long forgotten, and the caliph therefore chose what seemed to be a likely spot and set his men to forcing a new entry—a task they accomplished with the help of a large slice of luck.

Popular Science magazine, in 1954, put it this way:

Starting on the north face, not far from the secret entrance they had failed to find, Al-Mamun’s men drove a tunnel blindly into the pyramid’s solid rock…. The tunnel had progressed about 100 feet southward into the pyramid when the muffled thud of a falling rock slab, somewhere near them, electrified the diggers. Burrowing eastward whence the sound had come, they broke into the Descending Passage. Their hammering, they found, had shaken down the limestone slab hiding the plugged mouth of the Ascending Passage.

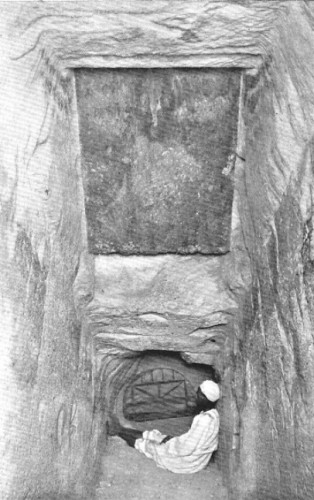

It was then, modern accounts continue, that Ma’mun’s men realized that they had uncovered a secret entrance. Tunneling around the impenetrable granite, they emerged in the Ascending Passage below the Grand Gallery. At that point, they had defeated most of Khufu’s defenses, and the upper reaches of the pyramid lay open to them.

That’s the story, anyway, and—if accurate—it adds considerably to the mystery of the Great Pyramid. If the upper passages had remained hidden, what happened to Khufu’s mummy and to the rich funerary ornaments so great a king would surely have been buried with? Only one alternate route into the upper vaults exists—a crude “well shaft” whose entrance was concealed next to the Queen’s Chamber, and which exits far below in the Descending Passage. This was apparently dug as an escape route for the workers who placed the granite plugs. But it is far too rough and narrow to allow large pieces of treasure to pass, which means the puzzle of the King’s Chamber remains unresolved.

|

The granite plug blocking access to the upper portion of the Great Pyramid. It was the fall of the large limestone cap concealing this entrance that supposedly alerted Arab tunnelers to the location of Khufu's passages. |

Is it possible, though, that the Arab accounts that Egyptologists depend on so unquestioningly may not be all they seem? Some elements ring true—for instance, it has been pointed out that later visitors to the Great Pyramid were frequently plagued by giant bats, which made their roosting places deep in its interior; if Ma’mun’s men did not encounter them, that might suggest no prior entry. But other aspects of these early accounts are far less credible. Read in the original, the Arab histories paint a confused and contradictory picture of the pyramids; most were composed several centuries after Ma’mun’s time, and none so much as mentions the vital date–820 A.D.— so confidently stated in every Western work published since the 1860s. Indeed, the reliability of all these modern accounts is called into question by the fact that the chronology of Ma’mun’s reign makes it clear he spent 820 in his capital, Baghdad. The caliph visited Cairo only once, in 832. If he did force entry into the Great Pyramid, it must have been in that year.

How can the Egyptologists have got such a simple thing wrong? Almost certainly, the answer is that those who spend their lives studying ancient Egypt have no reason to know much about medieval Muslim history. But this means they do not realize that the Arab chronicles they cite are collections of legends and traditions needing interpretation. Indeed, the earliest, written by the generally reliable al-Mas’udi and dating to no earlier than c. 950, does not even mention Ma’mun as the caliph who visited Giza. Al-Mas’udi attributes the breaching of the pyramid to Ma’mun’s father, Haroun al-Rashid, a ruler best remembered as the caliph of the Thousand and One Nights—and he appears in a distinctly fabulous context. When, the chronicler writes, after weeks of labor Haroun’s men finally forced their way in, they:

found a vessel filled with a thousand coins of the finest gold, each of which was a dinar in weight. When Haroun al-Rashid saw the gold, he ordered that the expenses he incurred should be calculated, and the amount was found exactly equal to the treasure which was discovered.

It should be stated here that least one apparently straightforward account of Ma’mun’s doings does survive; Al-Idrisi, writing in 1150, says that the caliph’s men uncovered both ascending and descending passages, plus a vault containing a sarcophagus which, when opened, proved to contain ancient human remains. But other chroniclers of the same period tell different and more fantastical tales. One, Abu Hamid, the Andalusian author of the Tuhfat al Albab, insists that he himself entered the Great Pyramid, yet goes on to talk of several large “apartments” containing bodies “enveloped in many wrappers, that had become black through length of time,” and then insists that

those who went up there in the time of Ma’mun came to a small passage, containing the image of a man in green stone, which was taken out for examination before the Caliph; when it was opened a human body was discovered in golden armor, decorated with precious stones, and in his hand was a sword of inestimable value, and above his head a ruby the size of an egg, which shone like fire.

What, though, of the earliest accounts of the tunnel dug into the pyramid? Here the most influential writers are two other Muslim chroniclers, Abd al-Latif (c.1220) and the renowned world traveler Ibn Battuta (c.1360). Both men report that Ma’mun ordered his men to break into Khufu’s monument using fire and sharpened iron stakes—first the stones of the pyramid were heated, then cooled with vinegar, and, as cracks appeared in them, hacked to pieces using sharpened iron staves. Ibn Battuta adds that a battering ram was used to smash open a passage.

Nothing in either of these accounts seems implausible, and the Great Pyramid does indeed bear the scar of a narrow passage that has been hacked into its limestone and which is generally supposed to have been excavated by Ma’mun. The forced passage is located fairly logically, too, right in the middle of the north face, a little below and a little to the right of the real (but then concealed) entrance, which the cunning Egyptians of Khufu’s day had placed 24 feet off center in an attempt to out-think would-be tomb robbers. Yet the fact remains that the Arab versions were written 400 to 500 years after Ma’mun’s time; to expect them to be accurate summaries of what took place in the ninth century is the equivalent of asking today’s casual visitor to Virginia to come up with a credible account of the lost colony of Roanoke. And on top of that, neither Abd al-Latif nor Ibn Battuta says anything about how Ma’mun decided where to dig, or mentions the story of the falling capstone guiding the exhausted tunnelers.

Given all this, it is legitimate to ask why anyone believes it was Ma’mun who entered the Great Pyramid, and to wonder how the capstone story entered circulation. The answer sometimes advanced to the first question is that there is a solitary account that dates, supposedly, to the 820s and so corroborates Arab tradition. This is an old Syriac fragment (first mentioned in this context in 1802 by a French writer named Silvestre de Sacy) which relates that the Christian patriarch Dionysius Telmahrensis accompanied Ma’mun to the pyramids and described the excavation that the caliph made there. Yet this version of events, too, turns out to date to hundreds of years later. It appears not in the chronicle that De Sacy thought was written by Dionysius (and which we now know was completed years before Ma’mun’s time, in 775-6 A.D., and composed by someone else entirely), but in the 13th century Chronicon Ecclesiasticum of Bar-Hebraeus. This author, another Syrian bishop, incorporates passages of his predecessor’s writings, but there is no way of establishing whether they are genuine. To make matters worse, the scrap relating to the pyramids says only that Dionysius looked into “an opening” in one of the three monuments of Giza—which might or might not have been a passage in the Great Pyramid, and might or might not have excavated by Ma’mun. This realization takes us no closer to knowing whether the caliph really was responsible for opening the pyramid, and leaves us as dependent on late date Arab sources as we were before.

As for the story of the falling capstone–that remains an enigma. A concerted hunt reveals it first appeared in the middle of the 19th century, published by Charles Piazzi Smyth. But Smyth does not say where he found it. There are hints, which I still hope to run to ground some day, that it may have made its first appearance in the voluminous works of a Muslim scientist, Abu Salt al-Andalusi. Abu Salt likewise traveled in Egypt. Very intriguingly, he picked up much of his information while held under house arrest in an ancient library in Alexandria.

The problem, though, is this: even if Smyth got his story from Abu Salt, and even if Abu Salt was scrupulous, the Muslim chronicler was writing not in the 820s but in the 12th century. (He was imprisoned in Egypt in 1107-11.) So while there may still be an outside chance that the account of the falling capstone is based on some older, now lost source, we certainly can’t say that for certain. It may be equally likely that the story is a pure invention.

You see, the forced entry that has been driven into the pyramid is just a little too good to be true. Put it this way: perhaps the question that we should be asking is how a passage dug apparently at random in a structure the size of the Great Pyramid emerges at the exact spot where the Descending and the Ascending Passages meet, and where the secrets of the upper reaches of the pyramid are at their most exposed.

Coincidence? I hardly think so. More likely someone, somewhere, sometime knew precisely where to dig. Which would mean the chances are that “Ma’mun’s passage” was hacked out centuries before the Muslims came to Egypt, if only to be choked with rubble and forgotten—perhaps even in dynastic times. And that, in turn, means something else: that Khufu’s greatest mystery was never quite as secret as he’d hoped.

Sources

Jean-Baptiste Abbeloos & Thomas Lamy. Gregorii Barhebræi Chronicon Ecclesiasticum... Louvain, 3 volumes: Peeters, 1872-77; Anon. ‘Observations relating to some of the Antiquities of Egypt…’ Quarterly Review XXXVIII, 1818; JB Chabot. Chronique de Denys de Tell-Mahré. Quatrième partie. Paris, 2 vols: É. Bouillon, 1895; Okasha El Daly, Egyptology: The Missing Millennium: Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings. London: UCL, 2005; John & Morton Edgar. Great Pyramid Passages. Glasgow: 3 vols, Bone & Hulley, 1910; Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne. Memoirs of Napoleon Bonaparte. Edinburgh, 4 vols: Constable, 1830; John Greaves. Pyramidographia. London: J. Brindley, 1736; Hugh Kennedy, The Court of the Caliphs: the Rise and Fall of Islam’s Greatest Dynasty. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004; Ian Lawton & Chris Ogilvie-Herald. Giza: The Truth. London: Virgin, 1999; Mark Lehner. The Complete Pyramids. London: Thames & Hudson, 1997; William Flinders Petrie. The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh. London: Field & Tuer, 1873; Silvestre de Sacy. ‘Observations sur le nom des Pyramides.’ [From the “Magasin encyclopédique.”]. Paris: np, 1802; Charles Piazzi Smyth. Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid. London: Alexander Strahan, 1864; Richard Howard Vyse. Operations Carried Out at the Pyramids of Gizeh in 1837. London, 3 vols: James Fraser, 1840; Robert Walpole. Memoirs Relating to European and Asiatic Turkey. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown, 1818; Witold Witakowski, The Syriac Chronicle of Pseudo-Dionysius of Tel-Mahre. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiskell International, 1987; Witold Witakowski (trans), Pseudo-Dionysius of Tel-Mahre Chronicle (Also Known as the Chronicle of Zuqnin). Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1996.

dangerous existence; as evidenced by the fact

dangerous existence; as evidenced by the fact

devolved into anarchy. The monasteries preserved the intellectual legacy of Rome as well as the text of the Bible while simultaneously nurturing scholarship and the desire to maintain moral values.

devolved into anarchy. The monasteries preserved the intellectual legacy of Rome as well as the text of the Bible while simultaneously nurturing scholarship and the desire to maintain moral values.  When thirty days had passed after his death, my heart began to have compassion on my dead brother, and to ponder prayers with deep grief, and to seek what remedy there might be for him. Then I called before me Pretiosus, superintendent of the monastery, and said sadly: 'It is a long time that our brother who died has been tormented by fire, and we ought to have charity toward him, and aid him so far as we can, that he may be delivered. Go, therefore, and for thirty successive days from this day offer sacrifices for him. See to it that no day is allowed to pass on which the salvation-bringing mass is not offered up for his absolution.' He departed forthwith and obeyed my words.

When thirty days had passed after his death, my heart began to have compassion on my dead brother, and to ponder prayers with deep grief, and to seek what remedy there might be for him. Then I called before me Pretiosus, superintendent of the monastery, and said sadly: 'It is a long time that our brother who died has been tormented by fire, and we ought to have charity toward him, and aid him so far as we can, that he may be delivered. Go, therefore, and for thirty successive days from this day offer sacrifices for him. See to it that no day is allowed to pass on which the salvation-bringing mass is not offered up for his absolution.' He departed forthwith and obeyed my words.