By Matthew Loving (Translator) | MHQ Departments | Published: August 03, 2011 at 12:03 pm

In September 1870, at the height of the short Franco-Prussian War, more than 200,000 Prussian troops and cavalry opened what would become a five-month siege of Paris. Most of the troops of Napoleon III were captured or bottled up elsewhere, but before their inevitable surrender, Parisians led by such notables as Victor Hugo raised a spirited defense. The Louvre was emptied of its treasures and converted to an armory, and city leaders cleverly found military uses for civilian businesses and pastimes. Among their innovations: using balloons to carry mail and military dispatches over enemy lines.

Not yet a century old, balloon travel was a French specialty, with Paris home to the vaunted Vaugirard balloon factory. Gaston Tissandier—a chemist, adventurer, and ballooning pioneer—quickly volunteered for the hazardous messenger duty. The cargo on his first trip included more than 175 pounds of letters, as well as a few carrier pigeons to deliver return mail to the city. Tissandier recorded this flight in his memoirs, In a Balloon! During the Siege of Paris: Memories of an Aeronaut, translated into English for the first time here. The excerpt has been edited for space and readability.

On September 30, at 5 in the morning, I left home with my two brothers. When we arrived at the Vaugirard factory floor, my balloon lay there on the ground like an old lump of rags. It was the Céleste, a small balloon of 900 cubic yards that had been generously donated by its owner in support of the military cause. I bent down to make a closer inspection.

Damn it all! What a deplorable state of disrepair! There had been a deep freeze the night before and the cold had set in to the balloon's fabric, making it hard and in places cracked. Great God! And what did I spy adjacent to the intake valve? Holes large enough to run your fingers through. Farther up, the envelope was riddled with a constellation of punctures. This wasn't a balloon; it was a soup strainer.

It was only a matter of seconds before I heard somewhere below the basket the hiss and whirl of bullets and the discharge of even more shots

Just the same, the flight crew soon arrived to inflate and ready the airship. Working with these men was a skilled tailor from the city who, armed with his needle, began dutifully repairing the damage. One of my brothers brought out a pot of glue and a pencil and began applying paper bandages to the small holes that presented themselves to his meticulous investigation.

What did it really matter? I was only moderately mollified by these ambitious efforts. The truth was, I was to leave very shortly in this cruel contraption, crumbling with age and misuse.

My thoughts were suddenly shattered by the crack of cannons at the city gates; my mind envisioned the Prussian guns that awaited my airship, ready to spit out rivers of bullets in my direction.

By 9 a.m. the balloon had been filled and the basket attached. I fastened on the extra ballast and loaded three batches of mail. A cage containing three pigeons made its way to my balloon.

"Look here," said Roosebeke, the man charged with their care. "Take care of my birds; upon landing offer them both water and wheat seed."

As I climbed aboard my balloon, the cannons exploded once more at the city gates. I embraced my brothers and friends and thought of the soldiers fighting and dying only steps away. My soul filled with the cry of the country in need; my destiny now was to deliver what had been entrusted to me. This was my solemn moment, and no other thought could delay me.

"Lâchez tout! Let her go!"

At 10 minutes to 10, I floated at an altitude of 3,000 feet, my eyes never letting go of the countryside below, where I observed a most disturbing sight that I will never manage to get out of my head as long as I live. There, where once existed the happy and animated outskirts of Paris, where boats passed slowly by and rowers waved their oars, a deserted expanse spread outward, stripped of all life and color. Not a man or a car to be found on the streets, no trains making their way over tracks. The ruins of bridges stood like vestiges of lost civilizations, not a single boat upon the steady Seine, who stayed true to her course, rippling across the now razed and bleak landscape. Not a soldier, not a sentinel, nothing, nothing, and as quiet as the grave! Like a stranger stumbling upon some forgotten city of old, it took some work to imagine again the two million souls trapped not far away behind the city's walls.

By 10 a.m., the sun's warming rays steadily increased my altitude; the gases within the Céleste, expanding in the heat of the new day, now began to seep out from valves just above my head, their strong, intermittent odors stunning me at times.

I then heard a slight rustling from the sides of the gondola and remembered my passengers, the pigeons, just now beginning to jostle their cages. They looked at me anxiously, perhaps fearing the worst.

The full sun with no cloud to obscure it shone upon the balloon, and the heat became stifling. I took off my overcoat and wished for a drink of water to quench my thirst. Managing to sit down on a pallet of mail, I rested my elbows on the edges of the gondola and contemplated in silence the great panorama that spread itself before me.

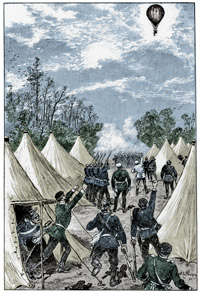

While a thousand thoughts raced through my mind, my compass reminded me the wind was continuing to pull me westward. After Saint-Cloud appeared Versailles, slowly revealing the wonders of its monuments and gardens. Up to that moment I had passed over only deserted ruins, but now the scene changed to a verdant park. Below I could make out Prussian camps. I was at 5,200 feet and well beyond the range of rifles. I armed myself with a spyglass and peered over the sides of the gondola for a closer look at the Lilliputian armies below.

Soon enough I spotted officers coming out from Trianon Palace. They watched me for quite some time until I noticed sudden movements in all directions. The agitated soldiers running back and forth appeared like ants on an upset mound, crisscrossing the same lawn where Louis XIV once strode. They were pointing up at the Céleste, and I relished the moment, knowing that in their anger and haste they were utterly powerless to stop the delivery of the parcels beneath me.

At that same moment I remembered the 10,000 proclamations printed in German that needed delivering. Grabbing a handful of these missives, I threw them overboard, where they spread out like leaves in flight and floated slowly down to earth. I bombarded the officers and soldiers below with hundreds upon hundreds of the tracts, saving the rest for the other enemy troops I was likely to encounter.

What did the salutation say? Simple words to the German armies that the French people were no longer burdened by emperors or kings and that if they were to show the same common sense and join us, we would no longer need to kill one another aimlessly like wild beasts. Strong words that fluttered lightly in the morning breeze.

Under an ardent sun, the Céleste maintained an altitude of 5,200 feet without my having to release an ounce of ballast; yet there was little doubt that the balloon was leaking, and without the exceptional atmospheric warmth of the day the poor craft would not remain long in the air and would soon enough fall quickly back to earth, perhaps in the middle of the Prussian hordes.

Tissandier and his brother, Albert, were renowned scientists and aviation pioneers (Henri Thiriat/Library of Congress).

Leaving Versailles I floated over a small forest. In the middle of the wood a distinct clearing had been cut, the ground tamped flat and a double row of tents erected on either side of the perfect parallelogram. I had only just passed over this camp when I suddenly noticed soldiers below making a formation; I could see clearly from that height the gleam and flash of bayonet tips as rifles were raised and all at once cracked out shots in a plume of smoke.

It was only a matter of seconds before I heard somewhere below the basket the hiss and whirl of bullets and the discharge of even more shots. Sure enough, after surviving the first hail of bullets I was soon greeted by a second and then another, and still yet another, one following the next in steady succession until the wind at last carried me away from that inhospitable place. For every round I had been subjected to, I had replied with a veritable deluge of leaflets rained down upon my attackers.

I did not care to hang around long enough to waste any more of the Prussians' gunpowder; other horizons awaited me. I was soon swiftly advancing toward a distant forest. I cannot say I was not somewhat concerned to notice that the Céleste was losing altitude; I began to jettison ballast bit by bit, with precious little to work with. Unfortunately at that moment I had not made it far at all from the outskirts of Paris. The warm welcome I had just received from the region's newest inhabitants did not bode well for a forced landing.

I have always noticed, and not without surprise, that the aeronaut even at considerable heights remains subject to the landscape over which he is flying. If he is hovering over the chalky hills of Champagne, he feels the intense warmth of the sun as reflected from the ground, like the passerby warmed by the sun that radiates from a whitewashed wall. Conversely, if he is sailing over the treetops of a forest floor, the air traveler finds himself surrounded in the cool humidity of the living things below, as if he were suddenly entering the coolness of a cave during the height of summer. This was precisely what I experienced at 10:45 that morning as I passed 4,700 feet above the treetops, which I soon recognized as the forest of Houdan. My compass and map left no room for guesswork. The sudden chill that I had felt after basking in the sun most of the morning was also felt by my balloon, which cooled and contracted, sinking toward the trees below as if the branches called out to it. Was the Céleste now like the bird in flight seeking a branch to alight upon?

I quickly emptied a ballast sack overboard but the barometer continued its descent; the cold now chilled me to the bone. The balloon descended to 3,300 feet, then to 2,600, then to 2,000. I emptied three of my ballast bags, only to level out at 1,600 feet above the treetops, with the balloon still refusing to gain altitude.

At that moment I found myself floating over the intersection of two roads. I could make out below a group of men who had assembled in the road. Grand Dieu! They were Prussians. And then farther along, more of them; and then uhlans [lancers] who were moving along the roads.

I had only one sack of ballast remaining. I threw into the void my last packet of proclamations. But the balloon had lost much of its gas; I was now floating a mere 1,400 feet above the ground, well within range of rifle shot. I kept a close watch beneath me. If a soldier raised his rifle in my direction, I was resigned to heave down a packet of letters on his head. Lightening my load in this way would have certainly helped my balloon find its wings again. No matter my desire to complete my mission in full; I would not trade my life for a pack of letters.

Lucky for me the wind was swift and I shot like an arrow over the treetops; the uhlans peered up at me, so astonished by my passing overhead that not a shot was fired. I continued on my way over verdant prairies hemmed in by aubepine hedges.

By noon I was barely passing a few hundred feet above the ground. The spectators who gathered beneath me now were clearly the French people of the countryside, as indicated by their blouses and sabots. They raised their arms as I passed overhead as if to call me to them; but being still close to the forest's edge, I preferred to sail on for as long I could maintain altitude. I contented myself by throwing out several stacks of Parisian newspapers to these good people.

Soon enough a small town rose upon the horizon. It was Dreux, with its tall, square tower. The Céleste descended quickly now, and this time I did not object. A cloud of townspeople soon ran after the still-hovering airship. I shouted down to them with all my might: "Are there any Prussians around here?"

A thousand voices responded in chorus: "Non, non, descendez! No! No! Come down!"

I was now no more than 160 feet above the ground, and my guide rope scraped over the tops of fields. But seized by a sudden wind, the balloon was abruptly caught up and sent on a collision course with a high adjacent hillside. The balloon briefly grazed the ground of the hilltop, causing a brutal shock that flipped the gondola completely upside down. I managed to take a good knock on the head that left me in some pain afterward. I could now see that the balloon was descending far too quickly for a landing, so at last I cut away the remaining ballast sack; yet I managed, in trying to do more than one thing at a time during a solo flight, to lose hold of the knife, the same knife I needed to release the balloon's anchor. I had no time to mourn this botched effort, as the Céleste had now leaped 200 feet into the air, only to immediately come crashing back to the earth; this time however, I succeeded in freeing the anchor and opening the main release valve. The balloon at last came to rest, and the people of Dreux, running out to see the commotion, surrounded me on every side. I had managed to foul my arm and earn a bruising bump on the head, but at last, I had also come to a full stop in friendly territory.

Ah! How happy I was to clasp the hands of all those who now surrounded me. They pressed me with questions of every sort. What has become of Paris? What do they think in Paris? Is Paris still resisting? To the best of my ability, I attempted to respond to the thousands of inquiries that came from every direction. I then gave a speech to mark the occasion.

"Yes, Paris is still holding its head up before her enemy. There is no sense in searching that valiant population for weakness or discouragement, for all one may remark in that great city is an unbroken tenacity and an enduring fortitude. If Provence would follow Paris, then France shall yet be saved!"

Then with haste I deflated the Céleste, while local guardsmen arrived to push back the gathering crowd. A carriage soon arrived for me and was loaded with my bags of mail dispatches and cages of pigeons. The poor birds had been shaken by the landing and were not yet back to their senses.

Making my way to the carriage I received no less than 50 invitations to lunch. I ate happily and with a good appetite and afterward asked to be driven to the post office with my sacks of Parisian mail.

I laid them upon the ground and could not help but feel a certain emotion. There beneath my eyes were 30,000 letters from Paris. Thirty thousand families would think of the balloon that carried over the clouds news of their besieged loved ones.