By Juan Cole | Published in History Today Volume: 40 Issue: 3 1990

Juan Cole looks at the pacifist, prophetic and millenarian 'world religion' whose leader emerged from the social and political unrest of 19th-century Iran and whose followers have since been persecuted by shah and ayatollah alike.

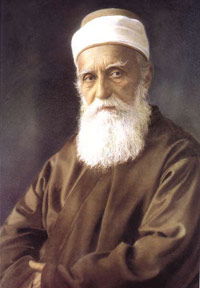

Abdu'l-Baha, son of Baha'u'llah and world leader of the Baha'i community from 1892 to 1921

As measured by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Islamic Republic of Iran has for the past decade achieved one of the worst human rights records of any country in the world. Of course, many of the government-sponsored summary arrests and executions carried out have targeted political groupings that posed an alternative to the clerical state. But the Khomeini regime has also persecuted communities that posed no particular threat to the Islamic Republic's stability, most prominently the Baha'is. The Baha'is, numbering some 3-400,000 in Iran, constitute the country's largest non-Muslim religious minority. The mullahs, or clerics, now in control have had nearly 200 of the most active Baha'i leaders executed, in addition to placing severe disabilities upon the religion's adherents. The Baha'is have responded to this persecution without violence, unlike most Iranian political groups. Although the past ten years have constituted the longest sustained bout of official persecution the Baha'is of Iran have faced, they have, since their religion's inception in the 1860s, encountered hostility arid occasional pogroms from the Shi'ite Muslim society in which they subsist. What is it about this small and ostensibly rather harmless group of people, who now constitute a little less than 1 per cent of Iran's population, that attracts the venom of the Shi'ite supremacists? What does the Baha'i religion stand for? Can Baha'is be classed as prophets without honour?

Religions of the Near East have arisen in conjunction with great political movements and transitions. Peoples of this area have for four millennia perceived their God to work in history. This history begins with creation, is informed by the confrontation between prophets and the powers that be, and has its climax in the advent of a messiah (or the return of a messiah already come). These elements are common to the major religions that have grown up in this region: Judaism, Zoroastrianism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baha'i faith. From the seventh century AD, Islam came to dominate the Near East, propounding a belief that the Prophet Muhammad had come to continue the work of the biblical prophets, from Abraham to Jesus of Nazareth. Many Muslims expressed, in their folk religion and even in learned commentary on the Quran, the expectation that two messianic figures would arise on earth before the resurrection day. The first of these, the Mahdi or 'rightly-guided' one, would descend from the Prophet Muhammad and would restore the world to justice after it had been filled with iniquity. The second, Jesus Christ, would thereafter return. Millenarian movements proliferated with especial vigour among the Shi'ite Muslims. The Imami Shi'ites believe that a line of Muhammad's descendants through his daughter, Fatimah, ought to have ruled the early Islamic state, hut that other dynasties unjustly shunted aside these leaders or Imams. They hold that the twelfth imam in the line of the Prophet's house disappeared into a supernatural realm from which he would some day return as the Mahdi. The line of imams prematurely ended, leaving the Shi'ites with no wholly legitimate ruler. Over time, the Shi'ite clergy asserted that in regard to religious functions they could stand proxy for the absent imam until his advent. After the Shi'ite Safavid dynasty conquered Iran in 1501, it sought the help of the clergy in converting Iran to that branch of lslam and in legitimising the new state.

Both this religious tradition and a set of political and social problems formed the background to the rise of the Baha'i faith. The shahs of the Qajar dynasty (1'?85-1925) promoted Twelver Shi'ism and a form of tribal feudalism in Iran. Shi'i clerics largely co-operated with the Qajar state, which in turn helped enforce Shi'i orthodoxy. The Qajars had the misfortune to rule over Iran at a time when it was being decisively incorporated into the capitalist world market and the European colonial and neo-colonial political system. Between 1804-14 and again in 1826-28 Iran fought wars with Russia that proved disastrous for Tehran, which lost territory, had to pay heavy indemnities, and had to agree to fixed low tariffs on imported goods. Anglo-Russian rivalry in Iran detracted from state sovereignty and impeded infra-structural development, as with the railways, for instance. Although Iran's foreign trade probably increased twelve times in the course of the nineteenth century, and its population doubled to nine million, its economic development did not match that of Egypt and Turkey, and it fell very far behind the industrialising North Atlantic states. Artisans and merchants faced stiff competition from imported manufactures and international joint-stock companies. From the 1860s, Iran underwent a series of economic disasters, including the devastation of its silk industry by a silkworm disease, a famine in 1872, and a global collapse in the price of silver, the base for Iran's currency. These developments created sectoral misery and acted as a brake on growth even though the economy continued slowly to expand.

Aside from social discontents, the immediate background for the rise of the Baha'i faith (Din-i Baha'i) lay in Shi'ite esoteric and millenarian movements. The year 1844 (or 1260 of the Muslim era) marked the thousandth anniversary of the disappearance of the Twelfth Imam. Adherents of the esoteric Shaykhi school in particular speculated that the Mahdi would arise in that year. Out of this millenarian ferment arose the Babi movement. Its founder, a young man from a merchant background in Shiraz, Sayyid 'Ali Muhammad, declared himself from 1844 to have some sort of extraordinary relationship with the Hidden Imam. At first he was proclaimed a 'gate' (bab) to the Twelfth Imam. He later said he was the return of the Imam Mahdi himself, and he asserted that divine inspiration led him to reveal a new holy book abrogating the Quran. He apparently approved of a slightly improved status for women, allowed the taking of interest on loans, and forbade non-Babi merchants to operate in certain areas of Iran. He interpreted doctrines such as the resurrection symbolically. As Abbas Amanat has shown, the Bab's religion spread rapidly, appealing to merchants, guildsmen and workers in Iran's cities and small towns, so that he may have had 100,000 adherents by 1849. But in that year he was officially pronounced a heretic. Clashes began to occur between Shi'ite and newly Babi quarters of some towns, necessitating the intervention of government troops. In 185O the Qajar state had the Bab executed, and intervened on the side of the Shi'ites in local conflicts. In 1852 Bahi leaders in Tehran attempted to have Nasiru'd-Din Shah assassinated in retaliation for his execution of their prophet, but failed. In response, the shah ordered a nationwide witch-hunt for Babis, hundreds of whom were tortured and put to death. Between 1849 and the mid-1850s some 5,000 Babis were killed.

The crisis in the nativist, radical and sometimes militant Babi movement formed the crucible for the rise of the Baha'i faith, a pacifist and cosmopolitan successor religion. The Nuri brothers, among the few nobles to have adopted Babism, emerged as the primary focus of authority after the Bab's death. The more prominent brother, and the eldest, Mirza Husayn 'Ali (entitled Baha'u'llah or the Glory of God, 1817- 92), cut an almost Tolstoyan figure. Repulsed by violence, concerned with the welfare of peasants, dedicated to spreading the new religion since its inception in 1844, he attracted the attention of the Qajar state. But his younger brother and ward, the teenaged Yahya Nuri (entitled Subh-i Azal or Morn of Eternity) was said to have been appointed the Bab's vicar in 1850. Baha'u'llah later maintained that Azal's appointment had been a ruse to draw fire from himself, the real leader. Baha'u'llah was exiled to neighbouring Ottoman Iraq in 1855 for his Babi beliefs, having been found innocent of involvement in the assassination plot. Azal joined his older half-brother in Baghdad, but remained under cover.

By the 1860s, many Babis, dissatisfied with Azal's furtive leadership and disappointed that their religion had gone underground, yearned for some new form of authority. The widespread expectation that Jesus would return after the advent of the Mahdi led many to speculate that a new theophany would soon appear. The Bah himself had spoken of a future prophet, 'One whom God would make manifest', who would arise to confirm or modify Babism. In 1863 Baha'u'llah revealed to a small group of relatives and friends that he was the promised one of the Bab. In the same year the Ottoman authorities responded to Iranian pressure by further exiling Baha'u'llah, first to Istanbul, and then to Edirne. Azal insisted on accompanying his older half-brother to Turkey. Between 1864 and 1867 Baha'u'llah began sending emissaries back to Iran with the news that he was the one whom the Bab prophesied God would make manifest. This proclamation met with an enthusiastic response among Babis, who began becoming Baha'is, or followers of Baha'u'llah, in great numbers. But it created a good deal of bitterness in Azal, who had become attached to the perquisites of religious authority. Constant Azali complaints led the frustrated Ottomans to separate the two brothers, sending Azal to Cyprus and Baha'u'llah to the pestiferous prison of Acre in Palestine.

Baha'u'llah first of all proclaimed himself to the Babis back in Iran, through quotation and exegesis of the Bab's works, as the messianic figure foretold by the Bab. Then, in the period 1866-72 he penned epistles to the kings and rulers of the world, including Queen Victoria, the Ottoman sultan, the Iranian shah, Napoleon III of France, the tsar, and the pope. These letters had two primary purposes. First, through the Palestine consulates he informed the rulers of his messianic role and urged them to heed his counsel. Baha'u'llah as the successor of the Bah (the Mahdi) had the status of the return of Christ. He wrote, ‘The river Jordan is joined to the Most Great Ocean, and the Son, in the holy vale, crieth out: "Here am I, here am I, 0 Lord, my God!"' He saw himself, in addition, as the fulfilment of all the great world religions.

Baha'u'llah not only made his second coming known to these rulers, but also put forth some general social teachings. In an era of absolutism, he favoured constitutional monarchy and world federalism, and often exercised an option for the poor. He commended the abolition of slavery and of serfdom, and wrote to Queen Victoria: 'We have also heard that thou hast entrusted the reins of counsel into the hands of the representatives of the people. Thou, indeed, hast done well...' Baha'u'llah called upon members of parliament in Britain and elsewhere to arise for the reform of society. He added, 'That which God hath ordained as the sovereign remedy and mightiest instrument for the healing of the world is the union of all its people in one universal cause, one common Faith.' During the tense period leading up to the Franco-Prussian war, he called upon the world's rulers to establish peace and to cease their ruinous military build-up, which they paid for through onerous taxes on the poor. He stigmatised such actions as 'a heinous wrong,' and urged lower, hearable taxes. He pointed out that if these rulers established peace, they would not need so many weapons, and urged them to accept this political, 'Lesser Peace', insofar as they had refused the 'Most Great Peace' that could have been achieved under the Baha'i banner.

Baha'u'llah's vision went beyond social reform within the framework of individual nation-states. He advised, 'Glory not in love for your country, hut in love for all mankind'. This world-mindedness, he thought, should be given a practical shape; he called for 'the holding of a vast, an all-embracing assemblage of men,' to he attended by the rulers and kings or their appointees. The global assembly 'must consider such ways and means as will lay the foundations of the world's Great Peace amongst men' and should determine that if any nation attacked another, all would combine to stop the aggressor. He also advocated the adoption of a world language and script: 'when this is achieved, to whatsoever city a man may journey, it shall be as if he were entering his own home.' Baha'u'llah felt that human disunity derived from religious and ethnic prejudice, which he wished to replace with toleration and unity. In this connection he abrogated the Islamic and Bahi principle of holy war (jihad), and even said it is better to he killed than to kill.

In a book written in 1875, Baha'u'llah's eldest son, 'Abdu'l-Baha, called upon Iranians to awaken from their slumber, and defended the importation of modern science and technology from the West. He argued for a limitation on the power of government officials, the establishment of representative, elected governmental institutions, the raising of the masses out of poverty, the improvement of Iran's infrastructure, and the setting up of a modern school system. Like his father, 'Ahdu'l-Baha advocated global disarmament, the founding of a global assembly, and the renewal of religion to combat Voltairean atheism.

The radical nature of these proposals at the time they were made must be emphasised. The Ottoman sultans avoided calling a parliament in the nineteenth century, except briefly in 1877-78. Nasiru'd-Din Shah of Iran experimented with cabinet government in the early 1870s, but decided against it, and never countenanced talk of constitutions and parliaments. Central and Eastern Europe also subsisted under authoritarian regimes. Arms reduction, lowering regressive taxes on the poor, and the calling of a world assembly, likewise, would have found few advocates in most councils of state in the early 1870s.

Baha'u'llah's message, then, struck a responsive chord among the Babis back in Iran, nearly all of whom became Baha'is. J.D.Rees of the Indian civil service found in 1885 evidence of substantial Baha'i followings among the merchant class in Qazvin and among townspeople in Hamadan, Abadih, and Mashhad. The local leadership for the Baha'i community, which had no official clergy, often came from the urban merchant class. In addition to the Babis, Baha'u'llah attracted adherents from the Shi'ite middle strata, and from Iran's Jewish and Zoroastrian communities. The religion spread to India in Baha'u'llah's own lifetime, and soon after his death to the United States.

The rise of a new religion attracted the notice of Iranian governmental officials and of Shi'ite clergymen. The Qajar state feared Babism and remained suspicious of its successor. Furthermore, the Baha'i advocacy of a constitutional and parliamentary regime in Iran threatened the reactionary Qajar officials. Until the constitutional revolution of 1905-11, the Baha'is may have been the largest single Iranian group committed to constitutionalism and representative government, although their quietism and opposition to violence distinguished them from the revolutionaries. Third, the cosmopolitan outlook of the Baha'is encouraged them to establish links with Europe, learn languages, and engage in global commerce. In joining the comprador bourgeoisie, however, the Baha'i mercantile clans differed little from other Iranian merchants, including the Shi'ites (a point Peter Smith has made). Still, the conservative Iranian elite formed an image of the Baha'is as social radicals, political progressives, and cultural traitors.

The Shi'ite clergy, on the other hand, saw the Baha'is as a dangerous heresy. Baha'is denied the clerical doctrine that God would send no prophets after Muhammad. They believed the Quran had been abrogated in favour of Baha'u'llah's Most Holy Book (al-Kitab al-Agdas). They developed their own distinctive rituals. Baha'is allowed their women an active role in society and did not believe in veiling or seclusion. They also denied important Muslim principles such as the legitimacy of holy war. Moreover, the Baha'is tended to question the need for a clergy in view of the spread of literacy, and these views threatened the very existence of a clerical class in Iran.

Government or clerical persecution of Baha'is, in addition to or in conjunction with lynch mobs, became a fairly common feature of Baha'i life in Iran. During Baha'u'llah's lifetime important instances of persecution occurred in Isfahan in 1874 and 1880, in Tehran in 1882-83, and in Yazd in 1891. In 1903, Shi'ite mobs conducted major pogroms against Baha'is in Rasht, Isfahan and Yazd. The advent of the modernising and secularising Pahlavi monarchy (1926-78) only slightly improved the position of most Baha'is, who still had to subsist in a hostile Shi'ite civil society. Indeed, Reza Shah launched his own crackdown on Baha'is in the late 1930, as a part of his general totalitarian programme. Muhammad Reza Shah for a time countenanced a brutal nationwide pogrom against Baha'is in 1955 led by the Shi'ite clergy and their sup porters in the parliament and armed forces. No Iranian government, in contrast to, say, Pakistan, ever recognised freedom of conscience or freedom of religion for Baha'is.

In the twentieth century the nature of Baha'i leadership changed greatly After the charismatic ministries of 'Abdu'l-Baha (1892-1921) and Shoghi Effendi Rabbani (1921-57), the Baha'is in 1963 elected a lay world governing body called the Universal House of Justice, in accordance with Baha'u'llah's instructions. The Baha'i faith became a mass movement among peasants in South America, Africa, and especially India from the late 1950s and early 1960s. Well-organised communities developed in most of the world's non-communist nations, and globally Baha'is came to number some 4.5 million by 1988, according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

The intensity of persecution under Khomeini stands in contrast to anything Iranian Baha'is have ever seen before, taking on an almost Kafkaesque ambience. Shi'ite clerics accused Baha'is who helped conduct Baha'i marriages of spreading prostitution, since they saw these marriages as illegitimate. They accused Baha'is who attended religious conferences in New Delhi or London of spying for imperialist powers. They branded Baha'is who donated funds to their headquarters in Israel Zionist supporters, even though none of this money in any way benefited the host country (a similar disapproval would not attach to the donation of funds to Arab Muslim causes in Israel). They arrested hundreds of Baha'i physicians, civil servants, university professors, merchants, and students. Some were simply made to disappear. Others they had tortured and executed. They asked bereaved families to bear the costs of the execution. Only in late 1988 did this oppression case up. They expropriated Baha'i properties, along with pension funds and children's bank accounts. Forced apostasies became common. They denied Baha'is ration cards, and refused their children admission to state schools and universities. They forbade them to leave the country. Although a couple of hundred executions and several times that many jailings do not constitute genocide, these actions aimed at the Baha'i community's extirpation in the long term.

Since the actual accusations against the Baha'is seem rather bizarre, many have searched for the latent reasons for their persecution. Anti-Baha'ism in Iran might best be compared to anti- Semitism in Europe. Like the Jews, the Baha'is are seen to symbolise threatening aspects of modernity. They are caricatured as corrupt financiers and as rootless cosmopolitans easily tempted into spying and treason for foreign powers. They adopt modern education and modern science with alacrity, producing large numbers of intellectuals, physicians, engineers and business people. If modernity menaces Iran's identity, they are surely accomplices. Indeed, the Iranian revolution in part constituted a struggle between the Shi'ite bazaar with its 'old' classes of petty commodity producers and marketers on the one hand, and on the other the new bourgeoisie and professional classes. Although Baha'is had more involvement in the petty commodity sector than is usually recognised, Iranians had formed an image of them as bourgeois.

Beyond the economic factors, Baha'is are, in the Shi'ite view, heretics. Just as the Jews denied central Christian doctrines, so the Baha'is introduced innovations into Muslim belief. Although they accepted that Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad had all been prophets, they refused to see in Muhammad the last prophet (and their universalism caused them to accept Krishna and Buddha, as well). They practised new rituals, and were seen to threaten the purity and modesty of Muslim women. Worst of all, they denied the authority of the Shi'ite jurisprudents. The current state is based precisely on the guardianship of society by the clergy, as deputies of the absent Twelfth Imam. To assert that the Twelfth Imam has already come, and has abrogated Islam, is ideologically to challenge the very foundations of the government. The caricatures and stereotypes hid the reality, that Baha'is constituted a mostly working- and middle-class community, consisting largely of law-abiding citizens with an unusual consciousness of global issues.

Baha'is' pacifism, belief in parliamentary democracy, commitment to religious universalism and toleration, and assertion of the compatibility of religion and modern science, all position them to play a role in the Third World similar to that attributed by Hugh Trevor-Roper to the Arminians in early modern Europe of nurturing the freedom of conscience necessary to the development of modern science and political society. Their grassroots commitment to seeing the emergence of a strong federal world government that could help prevent wars between nations marks them as a visionary group, perhaps p prophets. At least in Iran, they are certainly without honour.

Juan Cole is the author of Northern Indian Shi'ism in Iran and Iraq: Religion and State in Awadh, 1722-1859 (University of Californaia Press, 1988).

Further reading:

- Abdu'l Baha, The Secret of Divine Civilization, tr. M. Gail (Baha'i Publishing Trust, 1957)

- Baha'u'llah, Tablets of Bahaa'u'llah Revelaed after the Kitab-i-Aqdas (Baha'i World Centre, 1978)

- Mangol Bayat, Mysticism and Dissent: Socioreligious Thought in Qajar Iran (Syracuse University Press, 1982)

- Peter Smith, The Babi and Baha'i Religions: From Messianic Shi'ism to a World Religion (Cambridge University Press, 1987)