By James Barker | Published in History Today Volume: 62 Issue: 11 2012

Second World War Greece

Second World War Greece

James Barker describes the impact of an SOE mission in wartime Greece 70 years ago this month to demolish the Gorgopotamos railway bridge.Across the Greek Divide | History Today

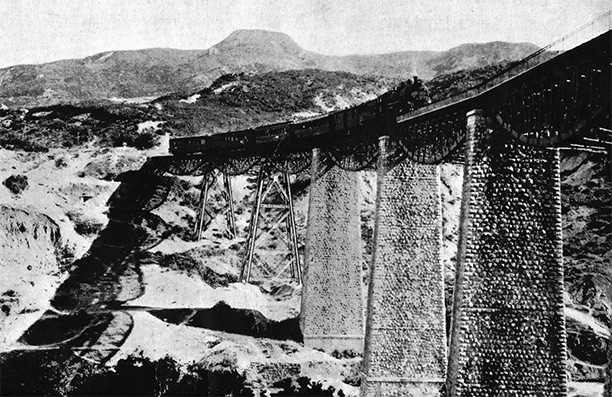

The Gorgonpotamos viaduct blown up in 1942 by SOE and subsequently rebuilt.One cold moonlit night in November 1942 saboteurs serving with the Special Operations Executive (SOE) blew up an important railway viaduct at Gorgopotamos in Axis-occupied Greece. The operation, code-named Harling, was intended to disrupt the flow of supplies to Rommel’s Afrika Korps in North Africa via Piraeus. Led by two British officers, Lt-Colonel E.C.W. Myers and his deputy, Major C.M. Woodhouse, the 12-man team included New Zealand and Indian combat engineers and Lieutenant Themistocles Marinos, its only Greek member. They were reinforced by three Cypriot and Palestinian escapees and 130 partisans from the Communist-dominated Ellinikos Laikos Apeleftherotikos Stratos (ELAS) or Greek National Liberation Army and their centre-right political foes, Ethnikos Dimokratikos Ellinikos Syndesmos (EDES) or the National Republican Greek League. Woodhouse had used his fluent Greek to persuade the field commanders of both these groups to discard their political differences and combine to fight the common enemy.

The raid on the night of November 25th succeeded in cutting the only railway line between Thessalonika and Piraeus for the next six weeks. Although it turned out to be the only time that ELAS and EDES ever fought together, this feat of arms motivated thousands of Greek men and women to join the partisans.

Afterwards SOE ordered Myers and Woodhouse to remain in Greece and mould ELAS and EDES into a unified guerrilla army. EDES quickly declared its willingness to co-operate but ELAS, by far the largest and best-organised Greek resistance movement, was wary of aligning itself with the British. The pro-Soviet orientation of its political wing, Ethnikos Apeleftherotikos Metopos (EAM) or the National Liberation Front, and the barely-concealed ambition of its collective leadership to seize power in Greece once the war was over posed a major challenge to British regional interests.

The other principal obstacle facing Myers and Woodhouse came from the British themselves. Churchill strongly backed the Greek monarchy. However, unlike other European heads of state exiled by Hitler, King George II of the Hellenes had no contact with any of the underground groups in his homeland. In the minds of many of his subjects the support that he gave to the crypto-fascist dictatorship of General Ioannis Metaxas in the years leading up to the Second World War had forfeited him the right to play any part in Greece’s future.

Civil war seemed inevitable. Myers and Woodhouse reckoned that they might be able to avert it by persuading ELAS’ middle-ranking commanders, many of whom were not Communists, to direct their firepower at the Axis occupiers rather than at EDES. Secondly, they urged EAM to enter talks with the Greek government-in-exile in order to agree on a plebiscite on the future of the monarchy once the war was over. By implicitly criticising British government policy Myers was treading on dangerous ground. Fortunately for him, he and his deputy saw eye-to-eye on this and all other important questions. Despite their different backgrounds, ‘Eddie’ Myers, a 36-year-old regular Royal Engineers officer, and ‘Monty’ Woodhouse, a Winchester and Oxford-educated classics scholar ten years his junior, formed a partnership that one historian has described as the most dynamic and effective in the five years of SOE’s existence.

By June 1943, with the help of an ever-expanding network of British liaison officers, they had succeeded in mobilising a Greek underground army roughly 20,000 strong. With this force Myers, now a brigadier, launched a series of highly-effective raids on Axis lines of communications throughout Greece, pinning down large numbers of German and Italian troops urgently needed elsewhere.

In July Allied troops landed in Sicily in the first phase of a campaign to knock Italy out of the war and open a new front in mainland Europe. Greece was now a strategic backwater as far as military planners in London and Washington were concerned, despite Churchill’s own preference for attacking Nazi Germany through the Balkans. The uneasy peace between ELAS and EDES now began to fall apart. In October 1943 fighting broke out between the two movements after talks, which Myers had arranged in Cairo, broke down between EAM representatives and the Greek government-in-exile. The following month Myers was sacked as head of the Allied military mission in Greece for daring to question Churchill’s continued support for the Greek monarchy.

Myers’ abrupt dismissal left Woodhouse (now the youngest Lt-Colonel in the British Army) with the lonely responsibility of protecting the lives of his British and American liaison officers caught up in the fratricidal conflict. He played a weak hand with skill. Not only did he persuade ELAS and EDES to agree to a ceasefire but he also personally convinced a sceptical Churchill during a weekend at Chequers in May 1944 to carry on supporting the Greek resistence fighters (andartes). When the Germans began their evacuation of mainland Greece in September 1944, ELAS and EDES joined British special forces in harassing the retreating enemy and in preserving important installations from ‘scorched earth’ demolition. The arrival of British troops on the Greek mainland shortly afterwards brought the curtain down on four years of brutal Axis occupation. In Woodhouse’s opinion, SOE’s mission in the country had been worthwhile – albeit at times only by the narrowest of margins. But he was powerless to prevent the outbreak of fighting between ELAS and British troops who had been ordered to disarm its members in December 1944.

The ensuing bloodshed in Athens, the restoration of the Greek monarchy and the 1946-49 civil war cast such long shadows over Greek society that another generation would elapse before some kind of reconciliation between Left and Right was possible. Today there is a memorial at Gorgopotamos next to the rebuilt viaduct, dedicated to the Greek andartes who took part in Operation Harling. It also serves as a reminder for Greeks, now experiencing exceptionally grave economic hardship, that courage and self-sacrifice can triumph over discord and disharmony, no matter how grim the circumstances.

James Barker is a television producer and historian of the British Empire

This entry was posted

at Saturday, October 20, 2012

and is filed under

1900 - 2000,

Europe

. You can follow any responses to this entry through the

.