By Adam Rovner | Published in History Today Volume: 62 Issue: 12 2012

This year marks the centenary of a forgotten effort to carve out a Jewish homeland in the vast Portuguese colony of Angola. Adam Rovner describes the little-known attempt to create a Zion in Africa.

Ephraim Moses Lilien designed this image for the Fifth Congress of Zionists in Basel in 1901. The angel points the oppressed Jew to a sun rising over a new life a new land.

In the autumn of 1902 Dr Theodor Herzl (1860-1904), the Austro-Hungarian author and prophet of modern political Zionism, found himself admitted to the corridors of power in Whitehall. Thanks in part to the efforts of his friend the Anglo-Jewish author Israel Zangwill (1864-1926) Herzl met the colonial secretary Joseph Chamberlain. Herzl found Chamberlain to be sympathetic to Jewish national aspirations. In April 1903 the two met again after Chamberlain had returned from a visit to British colonies in Africa, just weeks after state-sponsored attacks against Jews in tsarist Russia had shocked the world. Chamberlain fixed Herzl in his monocle and offered his help to the persecuted. ‘I have seen a land for you on my travels,’ Herzl recorded him saying of his rail journey across what today is Kenya, ‘and I thought to myself, that would be a land for Dr Herzl.’ Though Herzl was initially cool to the proposal, he recognised the significance of the offer. The world’s most powerful nation had acknowledged the six-year-old Zionist Organisation as the instrument of Jewish nationalism and offered land under the British Empire’s protection.

Herzl’s deputy in London continued to negotiate with Chamberlain on what erroneously came to be called the ‘Uganda Plan’. By mid-summer they had agreed on a draft charter for an autonomous settlement in the East African Protectorate. The solicitor and MP David Lloyd George drew up the document. Herzl announced the proposal at the opening of the Sixth Zionist Congress in Basel on August 23rd, 1903. According to the stenographic record of the Congress, the news was greeted with thunderous applause and Zangwill called out triumphantly: ‘Three cheers for England!’ One supporter recognised that the Rift Valley began in East Africa and ended in Palestine, thus linking the biblical homeland – albeit tenuously – to the British territory on offer. But Herzl admitted in a speech to the congress that the planned ‘New Palestine’ in Africa could not take the place of Zion. Still he urged an exploration of the territory.

A three-member Zionist commission sailed for East Africa in December 1904. Herzl did not live to see the expedition set off; he had suffered a fatal heart attack five months earlier. On the commission’s return the members published a generally negative report on the possibilities of mass settlement in the Guas Ngishu Plateau of western Kenya. The Seventh Zionist Congress convened in Basel in 1905 to discuss the pessimistic findings. Zangwill still championed the acceptance of British suzerainty over a Jewish territory in East Africa, but without Herzl’s leadership the majority of delegates now stood in opposition. At a rancorous emergency session Zangwill and his allies failed to muster the necessary votes to pursue the plan. ‘If we decline the East Africa project,’ Zangwill warned the congress, ‘we will experience the relief one has after the removal of a painful tooth. But we will recall, too late, that it was our last tooth!’

Embittered, Zangwill split from what he considered to be a toothless Zionism. He formed a popular rival body, the international Jewish Territorial Organization, known by its acronym ITO. The patriotic Zangwill believed that the Zionist movement had snubbed His Majesty’s Government and had rejected Herzl’s universalist vision of Jewish nationalism. He was also convinced that the Arab inhabitants of Ottoman Palestine presented a formidable obstacle to the resettlement of Jewish ancestral lands. Instead the ITO platform called for the establishment of a ‘great Jewish Home of Refuge’ elsewhere in the world, preferably under the British flag. Zangwill referred to this fantasy paper state as ‘ITOland’. He continued to seek an ITOland in East Africa, but also considered Australia, Libya and Mesopotamia (Iraq).

In 1907 Zangwill’s tireless agitation for the ITO cause came to the attention of an engineer and Boer War veteran John Norton-Griffiths, known popularly as ‘Empire Jack’ for his ultra imperialist views. Norton-Griffiths (1871-1930) held a contract to construct a railway that would stretch from the Angolan harbour of Lobito up through the highlands of the Benguela Plateau, eastward toward the desolate edge of what the Portuguese termed o fim do mundo – the end of the world – and then northward through the rich copper fields. Norton-Griffiths notified ITO representatives that the Portuguese in Angola put the needs of ‘white settlers’ first and he was certain that the ‘finest’ and ‘most suitable’ part of the ‘whole of Africa’ for Jewish settlement was Angola. But Zangwill rejected the idea, fearing that the ‘four million blacks’ thought to live there would ‘prevent any real colonization by doing all the dirty work’. For Zangwill, Jewish agricultural and industrial settlement, whether in Palestine, Angola or elsewhere, must be geared toward self-reliance, not exploitation.

With no promised ITOland on the horizon Zangwill began working with an American banker, Jacob Schiff, on an ambitious plan to resettle Russian Jews in the western United States. Between 1907 and 1914 approximately 7,400 immigrants did indeed make their way west through Galveston, Texas. Meanwhile, Zangwill had achieved massive success in the US with his play, The Melting Pot (1908), which popularised the metaphor of America’s multi-ethnic culture. Zangwill stated in the afterword to published editions of his play that its composition had been inspired by his frustrated efforts to find an ITOland. Then, after years of disappointment, the ITO received a letter in March 1912, written in French by a Russian Jew working for the Portuguese ministry of agriculture. The unknown correspondent, Wolf Terló, laid out his plan to settle ‘our miserable [Jewish] brothers’ on the healthy highlands of Angola, where each family of colonists would receive, free of charge, 500 hectares (approximately two square miles) of land. Terló claimed that his proposal had support from key parliamentarians and governmental ministers in the young, left-leaning Portuguese Republic.

After an exchange of letters, the ITO dispatched a delegation to Lisbon headed by the Russian jurist, Jacob Teitel. A man of many contradictions, the brilliant Teitel was the last remaining Jewish judge under tsarist rule, yet a friend of political radicals such as Vladimir Lenin and Maxim Gorky. Teitel’s son had met Terló in Rome and discovered that the families were distantly related. Terló subsequently invited his distinguished relative to Lisbon. When Russian ITOists learned of Teitel’s upcoming European travels, they asked him to assess the mysterious Terló’s character and the seriousness of his proposal. At the time Terló was a paunchy civil servant of about 40. After the Jews were expelled from Moscow in 1891 Terló had travelled to Jaffa and enrolled in an agricultural school. Later he studied wine-making in Bordeaux and after much wandering settled in Lisbon in 1904. There he organised an oenological council and found employment in the agricultural ministry. Terló’s sincerity in working to relieve Russian-Jewish misery was matched only by his confusion regarding the conflicting aims of Zionism and ITOism. Terló had originally approached the Zionist Central Bureau in Berlin about his Angola scheme. They recognised the significance of Portugal’s willingness to cede territory for mass Jewish immigration but rebuffed Terló’s overtures. Nevertheless the Berlin Zionists corresponded with Terló well into 1912, continuing to press him for inside information regarding the ITO’s designs on the colony.

In Lisbon Teitel arrived at Terló’s home to find a large map of Angola hanging on the wall. There he also met Terló’s partner in advancing the proposal, Dr Alfredo Bensaúde (1856-1941). Bensaúde was a leading scientist, founder and director of the Instituto Superior Técnico and the scion of a Jewish family from the Azores. The energetic Terló and the influential Bensaúde managed to sway a host of Portuguese politicians to the cause of Jewish settlement in Angola. Favourable newspaper coverage soon followed. By May representatives of the lower house of Portugal’s parliament, the chamber of deputies, actively debated the scheme. Teitel examined Terló’s and Bensaúde’s plan and came to the conclusion that ‘five or six hundred thousand’ Jews might settle the highlands of Angola’s Benguela province. ‘I would be happy’, he informed journalists, ‘if the last years of my life were dedicated to this cause.’

Cartoon of Portugal offering Angola as a second bride to widowed Israel, from a Yiddish satirical weekly published in New York, June 1912

Thus reassured, Zangwill arranged two long interviews with Sir Arthur Hardinge, Britain’s minister to Portugal. By coincidence Hardinge had served as commissioner of the East African Protectorate just before Chamberlain’s offer to the Zionists of territory there. He was thus well-acquainted with the abortive efforts at Jewish colonisation in Africa and was sceptical of ITO plans. Hardinge reported to his superior, the Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey (1862-1933) that he was ‘surprised that the scheme should be revived … but the previous discussions showed that Mr Zangwill and his friends were quite impractical people’. At one point Zangwill questioned Hardinge about ‘secret Anglo-German arrangements … respecting the Portuguese colonies in Africa,’ but the career diplomat quickly ‘turned [their] talk into another channel’. Zangwill was alluding to a secret agreement of 1898 to divide Portuguese colonies between England and Germany. The two powers sought a reconciliation in the years leading up to the First World War and their efforts centered on a mutually beneficial renegotiation of the 1898 accord. Zangwill reasoned that Portugal, debt-laden and in disarray following the fall of the monarchy in 1910, looked to maintain its hold on Angola with the help of Jewish settlers, who would then protect the colony’s integrity for the motherland. Yet he feared that should Portuguese rule be dissolved, his ITOland would fall into German hands under the terms of the secret conventions then being debated. Zangwill’s dream of an African Zion held out danger, as well as hope.

On June 20th, 1912 the Portuguese chamber of deputies passed the final version of bill number 159 to authorise concessions to Jewish settlers. Its articles clearly indicate the republic’s desire to use Jewish immigration to consolidate its hold over Angola. Colonists wishing to settle the Benguela Plateau would immediately become naturalised Portuguese citizens at their port of entry upon payment of a nominal fee. While this aspect of the bill would have appealed to impoverished Jewish refugees, other articles seemed designed to discourage immigration. No ‘benevolent society’ in charge of colonisation – like the ITO – could have a ‘religious character’ and Portuguese was to be the exclusive language of instruction in any schools the Jewish colonists might build.

Zangwill and the ITO delegates gathered in Vienna to discuss the Portuguese concessions. They knew that the bill’s restrictive clauses would prevent the establishment of a distinctly Jewish colony. After much discussion the ITO cabled its respectful rejection of the offer to the chamber of deputies, while holding out the possibility of continued negotiations. When Hardinge learned of the ITO decision he reported back to Grey that ‘unless – which is most unlikely to happen – the Portuguese Government were to give very large political powers to the new Jewish Colony, Mr Zangwill and his friends do not think its offer worth entertaining.’ But Hardinge neglected to mention, or was unaware, that the ITO had unanimously voted to send an expedition to Angola to examine the region proposed for Jewish colonisation.

Zangwill contracted with one of the most distinguished explorer-scientists of his day, John Walter Gregory (1864-1932), to head the ITO commission to the Benguela Plateau. Gregory, a geologist and Fellow of the Royal Society, had coined the term ‘Rift Valley’ and had travelled through Libya in 1908 on behalf of the ITO. Though not Jewish himself, Gregory had been associated with the ITO since its founding. His wife and Zangwill’s wife, the suffragist Edith Ayrton (1875-1945), were cousins who enjoyed a close relationship and so Gregory was trusted to survey the proposed Angolan ITOland. Gregory enlisted to the expedition his friend, Dr Charles J. Martin, head of the Lister Institute for Preventative Medicine in London. On the night of July 16th, 1912 Gregory formalised his agreement with Zangwill and the next morning wrote to a contact at the Colonial Office to enquire:

(1) whether there are any political considerations which would be liable to stop the establishment of a Jewish colony in the highlands of Southern Angola.

(2) whether there is any special area we should avoid or which we could not more safely select.Gregory’s letter was redirected to the Foreign Office, where he met an undersecretary and provided him with a description of ITO plans to ‘form a large colony of Jews who could live together and preserve their own religious and social rites in freedom’. Gregory requested letters of introduction to Hardinge in Lisbon and to British consular officers in Angola. In return he offered to ‘secure any information that might be useful’ to the British government during his travels through the colony. But Grey blocked Gregory’s request, indicating that the Angola plan was strictly an internal matter for the Portuguese government.

The Foreign Office was understandably reluctant to involve HM Government in Portuguese colonial affairs. While the ITO focused its efforts on Angola, the Foreign Office became embroiled in a public dispute with the British Anti-Slavery Society, which charged that Angolans were subjected to forced labour that amounted to slavery. These indentured labourers (serviçais) toiled under miserable conditions on cocoa plantations in the Portuguese island of São Tomé in Africa’s Gulf of Guinea. British officials were aware of abuses and of Portugal’s inability to stop them, but a series of books, pamphlets and exposés revealed the misery of the serviçais to the public and created a diplomatic scandal. Zangwill knew of Portugal’s shameful record on slavery and promised a concerned ITO confidante that ‘if we came in [to Angola] we should just hope to do away with those conditions’. He also wrote to Bensaúde to indicate that a successful ITO venture would help dispel the negative publicity Portugal received in the British press. Zangwill must have hoped that an appeal to Bensaúde’s patriotism would provide the momentum to submit a more attractive version of bill 159 for parliamentary approval. By this time Zangwill had come to rely on Bensaúde as his negotiator, fearing that Terló’s outspoken and public support for the scheme had damaged the ITO cause.

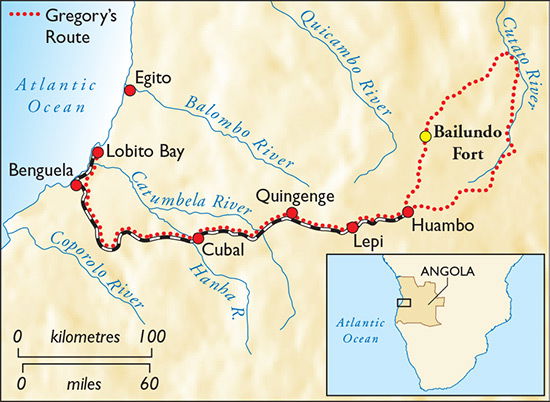

Map of Gregory's Angolan expedition. Click to expand. Angolans themselves were well aware of plans to populate their colony with Jews. The coastal capital of Benguela, with its grand Portuguese architecture and eucalyptus-lined boulevards, was home to an elite who welcomed the prospect of Jews thronging to the province. A series of articles penned by Angola’s foremost writer of the day, native-son Augosto Bastos (1872-1936), ran in the weekly Jornal de Benguela for more than a year. He reassured readers that Jewish colonists would not threaten Portuguese sovereignty because they would not have ‘cannons or an army behind them’. Later he urged Portuguese lawmakers to alter the terms of the colonisation bill so that it would be more attractive to the Jews. Bastos hailed the impending arrival of Gregory and Martin, believing that they ‘would soon be convinced’ that there was no place better than the Benguela Plateau to establish a home for ‘the persecuted [Jews] in Russia’.

Soon after Gregory and Martin arrived in Lobito, the terminus of the Benguela Railway, on August 22nd, 1912 they set off for the interior. Their caravan consisted of 32 natives, a headman, a cook, 25 porters, a ‘tent boy’, as well as another four aides. In all they spent five weeks surveying the plateau, travelling more than 1,000 miles by rail, wagon and on foot. Gregory noted in his published ITO report that oranges, bananas and coffee flourished and that ‘European vegetables grow luxuriantly’. He also found ‘ample timber for building’ and for fuel. Dr Martin considered the highlands to be ‘remarkably free from tropical diseases’ and to possess ‘a fine climate’ in which the ‘average European’ would maintain a ‘healthy and comfortable life’. Gregory concluded of the Benguela Plateau:

In view of its healthiness, fertility and attractiveness, and the ease with which the land could be acquired and developed, there seems no reason, if the Portuguese Government would grant a suitable concession, why successful European colonies should not be established.

Gregory’s report was intentionally vague as to the precise region to be colonised. But in a ‘highly confidential’ shipboard memo written as he steamed toward England fresh from his Angolan adventure he recommended that Zangwill petition the Portuguese for 5,000 square miles of land encompassing the town of Bailundo and the Cutato River valley northeast of Huambo. Today the region Gregory secretly selected for a Jewish homeland is Angola’s breadbasket, though minefields and wrecked armoured vehicles still dot a landscape scarred by decades of civil war.

Zangwill met Gregory and Martin on October 22nd, 1912 five days after they disembarked at Southampton. Once convinced of the practicality of founding an Angolan ITOland he wrote to the prominent banker and Jewish communal leader Leopold de Rothschild. Zangwill floated the idea of establishing an Angola Development Company that, he maintained, would attract twice as much capital ‘as [Cecil] Rhodes began Rhodesia on’. He also suggested that the ITO, with Rothschild’s help, might bring about a long desired rapprochement between England and Germany. One of the ITO’s geographical commissioners, the businessman and arts patron James Simon, was an intimate of the Kaiser, Zangwill noted to Rothschild: ‘And there thus seems to be an instrument to our hands ... to bring England and Germany publicly together’. A Jewish homeland in Africa, Zangwill believed, might serve the cause of peace in Europe. Rothschild, however, was unimpressed.

Bensaúde, Zangwill and Gregory nonetheless continued to promote the plan and on June 29th, 1913 the Portuguese senate revised and approved concessions for Jewish settlement. Gregory optimistically told reporters that the Benguela railway would eventually link up with the projected Cape to Cairo railway and thus ‘connect Angola to Europe’. Zangwill insisted to the press that Angola presented the best chance to achieve Herzl’s ambitions of a Jewish State ‘because [Angola] has no Christian influence, as does Palestine, nor does it have an Arab population, as does Palestine’. As for Bensaúde, he maintained pressure on governmental insiders, giving Zangwill to understand that the Portuguese ‘[g]overnment is ready to go over the heads of parliament and make a concession in accordance with Professor Gregory’s views, provided [the ITO] can show an adequate capital’. But funds were not forthcoming. Bensaúde expressed ‘infinite regret that the Societies which devote themselves to Jewish colonization cannot or will not conduct this Angola affair as it should be conducted’. Zangwill, too, was distraught at the short-sightedness of Jewish financiers who refused to form a land development company that ‘could provide thousands and ultimately millions of Jewish people with a home of their own’. Without territory the ITO could not obtain capital and without capital it could not obtain a territory. Momentum stalled for lack of finances and the required final vote on the colonisation scheme by both chambers of Portugal’s parliament never materialised.

By the end of 1913, many of Zangwill’s ITOists had begun to turn against the proposal. One former ally wrote to Zangwill that ‘the future Jewish Nation is more likely to be a worthy successor of the one which produced the Law and the Prophets if it is evolved in ... Palestine, than if it arises from a melting pot in Angola’. The cutting reference to Zangwill’s famous play was worthy of the author’s own wit, though it is doubtful he appreciated the swipe at his art. Zangwill saw rejection of Angola by Jewish magnates and fellow ITOists as ‘no less tragic a blunder’ than the refusal of land in East Africa nearly a decade earlier. ‘It shows,’ he concluded in an angry memorandum to the ITO, ‘that the Jews prefer to be landless and powerless’. Contact with Bensaúde limped on into the summer of 1914, before the eruption of the First World War. On the same day that the first clouds of poison gas wafted over allied lines, April 22nd, 1915, a despondent Zangwill confided to Gregory that the ITO had effectively come to an end: ‘I cannot pretend that much hope of an ITOland prevails in a planet so sundered from Reason and Love’.

The Angola scheme had been the ITO’s last and best chance to establish a territorial solution for Jewish homelessness. And Zangwill never forgot it, even after the 1917 Balfour Declaration issued during Lloyd George’s tenure as prime minister outlined support for ‘the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people’. Zangwill summed up the ITO’s failures in the pages of the influential Fortnightly Review two years later: Jewish history, he concluded, ‘is a story of lost opportunities’. Had he lived long enough to see the free nations of the world shut their gates to Jews fleeing Hitler’s Reich, Zangwill’s harsh verdict would surely have been tempered by a profound grief that his Angolan Zion never took root along Benguela’s fertile plateau.

Adam Rovner is Assistant Professor of English and Jewish Literature, University of Denver. He is the author of the forthcoming Promised Lands: The Global Search for a Jewish Home (New York University Press).