Keith Gessen The Guardian, Wednesday 12 March 2014

Frances Welch's new biography uncovers the humour and strangeness in Rasputin's fatal embrace of the Romanovs

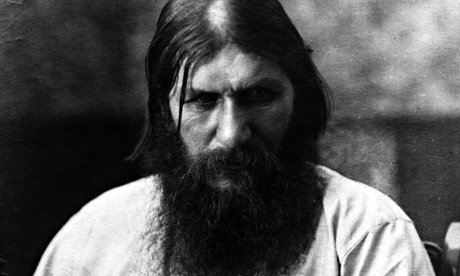

'Incredible charisma, bad teeth, questionable hygiene' … Grigory Rasputin. Photograph: BBC

Grigory Rasputin was a Siberian peasant turned holy man with incredible charisma, bad teeth, questionable hygiene (he claimed that he once went six months without changing his underwear), and a strong animal odour – like a goat's (according to the French ambassador). He used these various attributes to ingratiate himself with the royal family of Russia and become, for about a year toward the end of the Romanov dynasty, the de facto power behind the throne. While doing all this he seduced thousands of women and still managed to get stone drunk several nights a week. It's an inspiring story, though it ends badly, and no wonder that the expatriated French actor Gérard Depardieu has played Rasputin in not one but two biopics in the last two years.

As Robert Massie once wrote, only in Russia could the story of Rasputin have unfolded, but even in Russia it was pretty strange. In her humorous new biography, Frances Welch does not stint on its strangeness, though she does try to explain just how it came to pass.

Rasputin took advantage of the Russian tradition of the wandering peasant holy man, walking from village to village and reputed to have a direct connection with God (even Tolstoy, toward the end of his life, visited one). He also exploited the loneliness and isolation of the last Romanov couple, Nicholas and Alexandra – the tsar a polite, indecisive man and the tsarina a German-born and English-bred granddaughter of Queen Victoria ("The tsarina was as happy ordering chintzes from the latest Maples catalogue as she was cultivating mystics," writes Welch), who never quite adjusted to Russian life or shed her accent (she communicated with Nicholas in English). And, finally, he made use of the vexed condition of the couple's son, Alexis, the heir to the Russian throne, who had inherited (from Queen Victoria) a terrible disease: haemophilia. Nicholas and Alexandra kept vigilant watch over the boy, employed two sharp-eyed sailors to accompany him everywhere and commandeered an army of doctors to try to make him well. None of them could do anything; as Welch points out, they may easily have done more harm than good, prescribing, for example, the new wonder drug aspirin, which we now know is an anti-coagulant, the exact opposite of what a haemophiliac needs. The disease was torture for both the boy and his mother. During bleeding episodes Alexis would suffer excruciating pain, and his mother, an empress but also, she knew, the carrier of the disease, would sit by him, helpless.

The one person who appeared able to help was Rasputin. He was recommended to the family by their confessor, who had been impressed by his mixture of smelliness and religious fervour. Then it turned out that he seemed able to stop Alexis's bleeding. Exactly what Rasputin did has been the subject of medical dispute. During bleeding episodes, Rasputin would talk to the boy, tell him stories, calm him down – this may have lowered the heir's blood pressure, easing the bleeding. Contemporaries claimed that Rasputin could hypnotise people with his eyes, and it's possible he hypnotised Alexis, with the same calming effect. Rasputin was also the purveyor of some undeniably sage advice, as wise then as it is now: "Don't let the doctors bother him too much."

For Alexandra, there was no medical dispute: Rasputin was a Man of God. He became a frequent visitor to the royal household and the tsarina plied him with gifts and favours. Knowing of Rasputin's connection at court, people were always making requests of him, and a word from the empress went a long way in making those requests a reality. Rasputin's St Petersburg apartment became a busy office where he would meet supplicants, taking care of their medical problems with his healing powers and their bureaucratic problems with his influence. Payment could be made in money, pledges of loyalty, or, most controversially, "kisses".

During quieter times perhaps this all would have passed, but Russia was entering a period of intense crisis. In 1905, after a war with Japan ended in defeat and soldiers fired on a large protest in St Petersburg, Nicholas was forced to grant a constitution and convene a parliament, the Duma. But Nicholas granted the constitution against his better judgment, and when the Duma became too bold in its demands, he dispersed it. Another Duma was called, and also dispersed, and then another. Under the leadership of prime minister Pyotr Stolypin the country's economic performance improved rapidly. But Stolypin was assassinated in 1911. Russia soon found itself embroiled in the first world war, and less than four years later the entire royal family, including 13-year-old Alexis, was executed in a basement in Yekaterinburg.

The judgment of most historians is that the autocracy had no chance of surviving a war it could not win. And yet the war was won, eventually. What if Nicholas had held on another year? There's no question that some changes would have been in order. But he and his family may have had a different fate.

That they didn't can at least partly be attributed to Rasputin. His true nature – that of a drunk who made it a principle to start undressing every woman he met, until she made him stop – had become clear to people in St Petersburg relatively quickly, and soon Rasputin's relationship with the royal family became a scandal. The orthodox church, which had supported him, now tried to bring his behaviour to the attention of the tsar. It had no effect. Stolypin considered the question a sufficiently vital matter of state that he, too, presented a report: this also was ignored. And on it went. Rasputin had convinced Alexandra of his holiness, and no amount of evidence could turn her against him. All warnings about Rasputin came to seem like attacks on the family, and further isolated them from the people who wanted to help.

The worse things got, the more Alexandra came to rely on Rasputin's judgment. In the summer of 1915, with the war going poorly for Russia, Nicholas decided to leave the capital and assume command of the Russian army. This was a moderately bad idea militarily, but it was a disastrous idea for the government, which was left in Alexandra's hands. The tsarina was devoted to Russia, but inexperienced, and blinded by her belief in Rasputin. Under their joint direction a series of catastrophic decisions were made, as experienced ministers who disliked Rasputin were dismissed in favour of non-entities and incompetents. For years there had been (crazy) rumours that he and the empress were lovers; now people became convinced that they were also German spies.

Throughout all this, people kept trying to kill Rasputin. Welch lists at least four assassination attempts, including one by the female follower of a rival holy man, Iliodor, who stabbed Rasputin in the stomach. He survived. The final, successful attempt came in December 1916, and was carried out by a monarchist Duma deputy and two young aristocrats – one of them, Felix Yusupov, was the heir to Russia's largest fortune, and the other, Grand Duke Dmitry, was a nephew of the tsar. Yusupov lured Rasputin to his house, where he fed him poisoned cakes and wine, and, when these did not have their intended effect, shot him in the back. Rasputin, however, got up and started running away, at which point he was shot again by the Duma deputy. The conspirators then wrapped him in a curtain, bound his hands and threw him in a hole in the ice in the Neva river; he drowned.

They had hoped to save the autocracy, but if anything things became worse, and in any case it was too late. Just two months later crowds took to the streets of St Petersburg, and Nicholas was forced to give up the throne. In one of its few wise moves the provisional government dug up Rasputin's body and burned it. Not long after, the Bolsheviks seized power.

The story of Rasputin and his fatal embrace of the last Romanovs is a story of autocracy, of the kind of damage that can be wrought when a nation's fate depends too much on the judgment of a single individual. It's not easy to find contemporary analogues – Putin, for example, has no Rasputin – but I do keep thinking of Larry Summers, a man reviled in many circles, who nonetheless managed to ingratiate himself into the inner circle of President Obama's economic advisers early in his first term, when robust and equitable measures might have been taken to save the American republic – all of which Summers discouraged. But in that case, too, there probably wasn't much anyone could have done.