By Paul Crompton | Al Arabiya News

Saturday, 25 January 2014

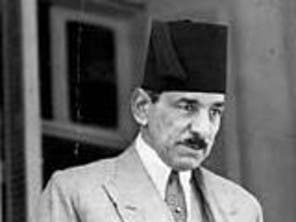

Since King Farouk was overthrown on July 26, 1952, his side of the story has seldom been told. (Photo courtesy of Nabila Nevine Halim / egyptianroyalty.net)

On July 25, 1952, King Farouk was trapped in his palace by revolutionaries, who then forced him into abdication and exile. The dramatic tale unfolds through a copy of the king's long-forgotten memoirs obtained by Al Arabiya News.

“The emperor allowed himself to be overthrown like a child being sent to bed,” wrote 18th century Prussian King Frederick the Great about Peter III, the 34-year-old Russian Tsar who was forced to abdicate after a coup by his wife Catherine.

Egypt’s 32-year-old King Farouk may have a similar story to his ouster. As the great-great-grandson of Muḥammad Ali, an Ottoman army commander of Albanian origins who seized control of Egypt in 1805, Farouk carried a long monarchical tradition that had evolved from Muhammad Ali’s ambitious military despotism to a modern, albeit weak constitutional monarchy.

And now, on July 25, 1952, he was racing through the streets of Alexandria in his Mercedes Benz at 80 mph with his wife, infant son, three daughters, an English nanny and aide-de-camp in tow, chased by the very military who had served him.

What had happened?

Several army officers, led by Gamal Abdel Nasser, an Egyptian deputy commander who would later become president of Egypt, sought to overthrow what they saw as a scandalous, corrupt, out-of-touch king. Known as the Free Officers Movement, their coup had been some time in the making.

Figurehead

To gain the respect of other non-involved officers, Nasser sought out Mohammad Naguib - a widely respected general - to spearhead the coup.

However, like everyone with power, Farouk had his sources of information. Shortly before his overthrow, the king got wind of the upcoming coup d’état and sent out orders of them to be arrested.

The plotters realized that there was no going back.

The eventful first day of the coup, July 23, has surprisingly mundane beginnings. As Farouk himself wrote in his memoirs, which were first published in serial form from Oct. 12, 1952 in a British Sunday weekly, Empire News: “A group of not more than 30-40 malcontent officers … were to walk casually into army headquarters one by one, and overpower the duty officers.”

Mohammad Naguib (C) and Nasser (L) pictured here shortly after the Free Officers took power in 1952 (File photo: Reuters) With the officers in control of most of Cairo's military, including army aircraft, Farouk had lost control of the capital in just one day. Now, on the 24th, the consolidated Free Officer-led army, was preparing for a military advance on Alexandria, a coastal city where the king was in residence. Upon their arrival in the city on the evening of the 25th, the officers announced a curfew that all people and vehicles on the streets of Alexandria would be fired upon.

Fateful drive

Farouk, who, on the 25th, had been staying at Montaza Palace while the coup had been brewing, decided that it had “become the perfect air target” for Free Officer-controlled bombers.

Instead, he quickly chose to take refuge in Ras el–Tin Palace in the heart of Alexandria, where “my people would see the Royal Flag of Egypt at my palace mast.”

After all, as Farouk said, he did not want rumours to abound that he had committed suicide.

A view of Ras el-Tin palace in Alexandria, where Farouk fled when the Free Officers seized the city (Photo courtesy of Ahmed Kamel / egyptianroyalty.net)

Packing his family into two cars, with a submachine gun resting on the knee of his aide-de-camp, Farouk sped through the empty streets - narrowly avoiding an encounter with two armoured cars - hoping to get to Ras el-Tin as fast as possible.

Shortly upon arrival, Farouk, his family, servants and around 800 army loyalists who had braved the drastic Officer-enforced curfew barricaded the entrance of the palace.

Farouk and his wife, Narriman, decided to rest. Then, when he later awoke and went to the balcony, he was fired on by two besieging Free Officers, whose bullets narrowly missed him.

Farouk was confused. “It was difficult to grasp the idea that a handful of revolutionaries had managed to seize the entire Egyptian army,” he wrote. He also faced a dilemma of whether to order his men to open fire on other officers in army uniform.

Farouk the marksman

Soon, however, the king’s loyal Sudanese guard returned fire, with Farouk, a self-professed skilled marksman, also choosing to grab a rifle.

In the ensuing gunfight, which would prove relatively non-lethal, the king “got three of them in the legs, and one machine gunner in the right shoulder. But it was sickening work, and I took no pleasure in it.”

Farouk, seen here in the 1930's bird hunting, described himself as an excellent marksman. (Photo courtesy of Ahmed Kamel / egyptianroyalty.net) If Farouk’s story of shooting back is true, it would make him possibly the most recent monarch to personally return fire against his attackers. (20 years before, Albania’s self-proclaimed monarch, King Zog, had shot at his would-be assassins while on a visit to Vienna. Coincidentally, Zog was Farouk’s card-playing partner when the former, by now exiled, lived in Egypt. And it was to Zog that Farouk - in his most famous quote - originally said: “Soon there will be only five Kings left-the King of England, the King of Spades, The King of Clubs, the King of Hearts, and the King of Diamonds.”)

Besiegers

While the besiegers had cut the palace phone line, the king was able to get through to his “loyal” prime minister, Ali Maher, on an emergency phone line he had kept “for just such emergencies.”

Farouk also called Jefferson Caffery, the U.S. ambassador to Egypt, and asked him to use all his influence to help the beleaguered royal family.

The U.S. stance towards Cairo at that time was not particularly positive, due to the American government’s dislike of Farouk. However, they did not want a massacre, and told the Free Officers to avoid bloodshed.

Caffery, who was aware of his duties to try and get the royals out of the country, told him that he “would raise heaven and earth to get them out of the country,” according to the king.

Some time later, a speeding car flying the U.S. flag with Caffery’s secretary inside was allowed into the palace by the “Naguibists,” with orders to stay with the royal family until the U.S. envoy had some assurance from the officers that their lives would not be in danger.

Cautious diplomacy

According to Anwar Sadat’s memoirs, sending only the secretary to the Ras el-Tin palace was “cautious” Caffery’s way of not antagonizing the rebels, and because he knew the king seemed to have lost.

Sadat then wrote up an official ultimatum in Maher’s office – that Farouk should abdicate in favour of his infant son, Crown Prince Ahmed Fuad, and leave Egypt later by six o’clock in the evening - the very same day - on July 26.

Ahmed Fuad, now Fuad II, is seen here with Farouk and Narriman, shortly into exile on the island of Capri, Italy. (Photo courtesy of Ahmed Kamel / egyptianroyalty.net) The revolutionaries were in a hurry, because as Nasser had told Sadat, “we want to get him out of the way quickly in order to have stability.”

Farouk, realizing he had no leg to stand on, and with an apparent sudden urge to protect his family, accepted the Officer’s ultimatum that a “trembling” Maher presented to him. He would abdicate, on condition that the abdication papers be formal and constitutional, and that he would be allowed to depart with full military honours.

The two conditions, Farouk said, were given for his son’s sake. By leaving Egypt with some degree of dignity, his story would not make “bitter reading” for when baby Fuad grew up.

It was arranged that the royal family would leave on the royal yacht, the Mahroussa, just six hours after Farouk signed his abdication.

Family ties

With this formal agreement signed, Farouk - now dethroned- now faced the difficult task of explaining the new, humiliating status quo to his wife, Narriman, and three young daughters, Farial, Fawzia and Fadia.

Narriman agreed instantly to accompany him on his uncertain departure, although, as Farouk had told her, doing so might mean she would never see her mother again. Fuad, who was now (technically) king, would travel with them.

Farouk’s daughters (from his ex-wife of nearly 11 years, Queen Farida) also agreed to join him.

This still, taken from a 1950's Egyptian film, depicts Farouk leaving Ras el-Tin palace upon his abdication (Photo courtesy of Ahmed Kamel / egyptianroyalty.net)

With the family in agreement to stay together, they turned to the urgent task at hand – packing their belongings. As they had left most of their clothes at Montaza Palace, they were only able to bring around a suitcase each of personal belongings.

After receiving Narriman’s beloved mother, Caffery and his personal assistant, and Maher, the premier, Farouk and his family, along with Fuad’s nurse, made their way to the quayside to depart on the Mahroussa.

‘Fanatical ones‘

The Free Officers kept their word that Farouk’s abdication would have some level of dignity befitting a monarch. Sadat arranged an aerial flyover salute for the king – who had donned his admiral’s uniform to show his respect for his loyal navy - while a consignment of soldiers, Naguib and several other Officers would see him off.

It is in this encounter that Farouk and Naguib meet. In the space of a day, one had become powerless, while one had become (at least theoretically) all-powerful.

Now dethroned, Farouk and his family left Egypt on

the Mahroussa, the massive Egyptian royal yacht (Photo courtesy of Ahmed Kamel / egyptianroyalty.net)“Little” Naguib, who arrived at the yacht just as they setting sail, came up to Farouk with a flushed expression.

“Sir, I am not responsible for this,” said Naguib, stepping on-board.

“There are others – fanatical ones – I was not called upon – I implore that you do not hold me personally responsible,” said the army general.

Farouk believed that these were the words of “a man being pushed too far from behind,” adding “I can only fear for his life now.”

Farouk’s prediction was not wholly accurate, but then not completely untrue. After being deposed by Nasser as Egypt’s first president less than three years later, Naguib would live under house arrest and was not allowed by to emerge from obscurity until Mubarak’s presidency began in 1981. After giving interviews on his brief time as president and penning his memoirs, Naguib died in 1984.

But on that fateful day, who was Naguib referring to?

Had he realized that he was merely a pawn in Nasser’s political game – or was he referring to the possible unseen hand in the coup, the Muslim Brotherhood?

To read the second part of the series, entitled “Did the Muslim Brotherhood overthrow Egypt’s King Farouk?” click here.

To view the entire seven-part series, visit the King Farouk: The Forgotten Memoirs homepage.

The overthrow of Egypt’s King Farouk: a dramatic departure from power - Al Arabiya News